If you’ve browsed a streaming service’s settings or shopped for a DAC, you’ve seen terms like FLAC, WAV, ALAC, and MQA. These are audio file formats, and they determine how your music is stored, compressed, and ultimately how it sounds.

The problem is that the terminology can feel a bit too much. Lossless, lossy, bit depth, sample rate. This guide breaks down what each format means, which ones qualify as hi-res audio, and which format is the best for different use cases.

What makes audio “Hi-Res”?

Before diving into formats, it’s helpful to understand what hi-res audio actually means.

Standard CD audio is encoded at 16-bit/44.1kHz. This was the benchmark for digital music quality for decades. Hi-res audio refers to anything that exceeds this specification, typically 24-bit audio at sample rates of 48kHz, 96kHz, or 192kHz.

The bit depth determines the dynamic range (the difference between the quietest and loudest sounds). The sample rate determines how many times per second the audio waveform is captured. Higher numbers in both mean more data, which translates to finer detail and a closer representation of the original recording.

Hearing the difference between 16-bit/44.1kHz and 24-bit/192kHz depends on your equipment and the quality of the original recording.

The three categories: Uncompressed, lossless, and lossy

All audio formats fall into one of three categories based on how they handle data:

Uncompressed formats store audio exactly as it was recorded with no compression at all. Maximum quality, maximum file size. Examples: WAV, AIFF.

Lossless formats compress the file to save space but preserve all the original audio data. When you play the file, it reconstructs perfectly. Think of it like a ZIP file for audio. Examples: FLAC, ALAC.

Lossy formats compress the file by permanently discarding some audio data. The result is much smaller files, but you lose information that can’t be recovered. Examples: MP3, AAC, OGG.

For hi-res audio, you want uncompressed or lossless formats. Lossy formats like MP3 don’t support hi-res specifications and lose data by design.

Hi-Res audio file formats

WAV (Waveform Audio File Format)

WAV is the standard uncompressed audio format developed by Microsoft and IBM. It’s the format CDs are encoded in, and it’s widely used in professional audio production.

WAV has maximum audio quality with no compression, and every device and software supports it. It can support hi-res specifications up to 32-bit/384kHz.

However, WAV has huge file sizes. A single hi-res album can easily exceed 2GB. Also, WAV files don’t handle album artwork, artist names, or track titles well.

So WAV is best for studio work and archival storage where space isn’t a concern.

AIFF (Audio Interchange File Format)

AIFF was Apple’s answer to WAV. It’s also uncompressed and offers identical audio quality. The main difference is better metadata support; you can embed album art and track information.

AIFF has native support on Apple devices. But it’s less universal than WAV outside the Apple ecosystem.

FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec)

FLAC is the most popular lossless format. It compresses audio to roughly 50-60% of the original WAV size without losing any data. When you play a FLAC file, it decompresses to the exact original.

Lossless compression means identical quality to WAV at half the file size. FLAC supports hi-res up to 32-bit/384kHz, it has excellent metadata support, and it is open-source and royalty-free.

FLAC is the best codec for building a hi-res music library. It offers the best balance of quality, file size, and compatibility for most listeners.

ALAC (Apple Lossless Audio Codec)

ALAC is Apple’s lossless format, essentially their equivalent to FLAC. It offers the same lossless compression with full Apple ecosystem integration.

ALAC has native support on all Apple devices and iTunes/Apple Music. The entire Apple Music lossless catalog uses ALAC.

It does have slightly larger files than FLAC in most cases, and limited support outside Apple’s ecosystem.

DSD (Direct Stream Digital)

DSD is a high-end format originally developed for Super Audio CDs (SACDs). It uses a different encoding method than the PCM-based formats above, a 1-bit stream at extremely high sample rates (2.8MHz, 5.6MHz, or 11.2MHz).

Many audiophiles consider DSD to offer a more natural, analog-like sound. It is mostly used in professional archival and mastering. However, DSD has very large file sizes, and it requires specific hardware and software to use.

MQA (Master Quality Authenticated)

MQA is a format designed to deliver hi-res audio efficiently over streaming. It uses a “folding” technique to package high-resolution data into smaller files that can be partially decoded on any device, and fully decoded on MQA-enabled hardware.

It has smaller file sizes than FLAC while delivering hi-res audio. It can also play on non-MQA devices with some reduced quality.

MQA is a proprietary format that requires licensing. MQA is quite controversial; some argue it is lossy, some say it is not. Tidal dropped MQA in favor of FLAC in 2024, and unless you have MQA-enabled hardware, FLAC is the way to go.

Lossy formats (Not Hi-res)

These formats don’t qualify as hi-res audio, but they’re worth understanding since you’ll encounter them constantly.

MP3

The format that started the digital music revolution. MP3 compresses audio by discarding data that the algorithm determines is less audible. At 320kbps (the highest common bitrate), quality is decent for casual listening. At 128kbps, the loss is noticeable.

AAC (Advanced Audio Coding)

Apple’s successor to MP3. It’s more efficient, meaning better sound quality at the same file size. It’s used by Apple Music (lossy tier) and YouTube.

OGG Vorbis

An open-source lossy format. Spotify uses OGG at up to 320kbps for its Premium tier.

Bit Depth and Sample Rate: What do the numbers mean?

You’ll see hi-res files or products like streamers and DACs labeled with specifications like “24-bit/96kHz” or “24-bit/192kHz.” Here’s what those numbers represent:

Bit depth determines dynamic range. The span between the softest and loudest sounds a recording can capture. 16-bit audio provides about 96dB of dynamic range, which covers most music comfortably. 24-bit extends this to around 144dB, well beyond what any speaker or human ear can reproduce. The practical benefit is more headroom during recording and mastering, which can translate to cleaner, more detailed sound.

Sample rate (measured in kHz) determines how frequently the audio waveform is captured. CD quality samples 44,100 times per second (44.1kHz). Hi-res files commonly use 48kHz, 96kHz, or 192kHz. Higher sample rates capture more detail in the upper frequencies, though the audible benefit above 96kHz is debated.

File size comparison

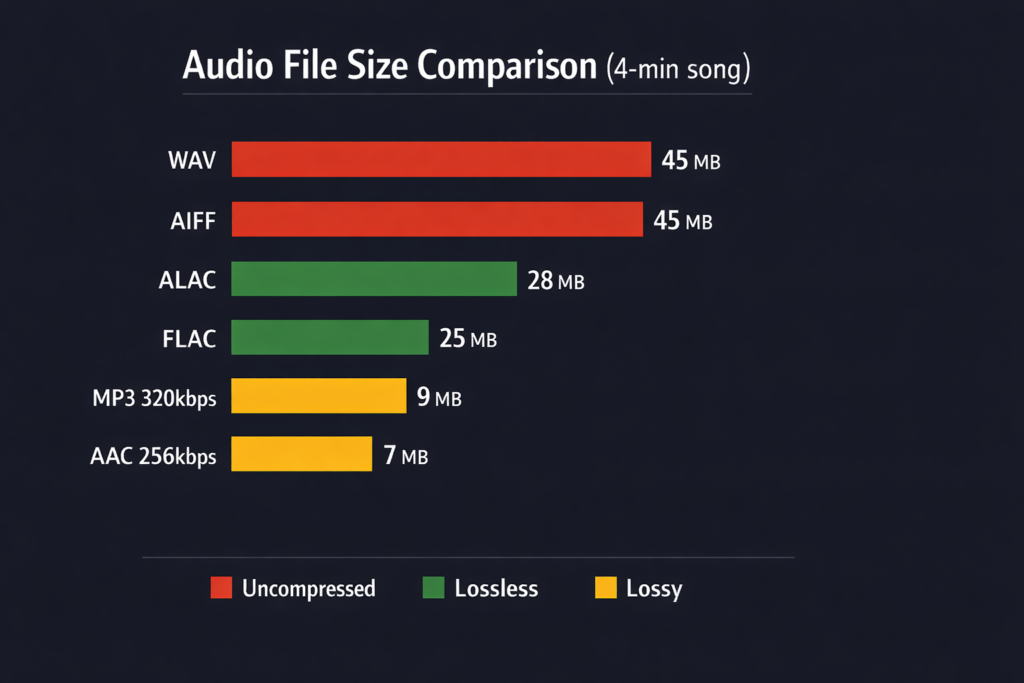

To put the size differences in perspective, here’s roughly what a 4-minute song looks like in each format at CD quality (16-bit/44.1kHz):

| Format | Approximate Size |

| WAV (uncompressed) | 40-50 MB |

| AIFF (uncompressed) | 40-50 MB |

| FLAC (lossless) | 20-30 MB |

| ALAC (lossless) | 20-35 MB |

| MP3 320kbps (lossy) | 8-10 MB |

| AAC 256kbps (lossy) | 6-8 MB |

At hi-res (24-bit/96kHz), the FLAC files jump to 50-80 MB per track, and WAV files can hit 150 MB or more.

Which format should you use?

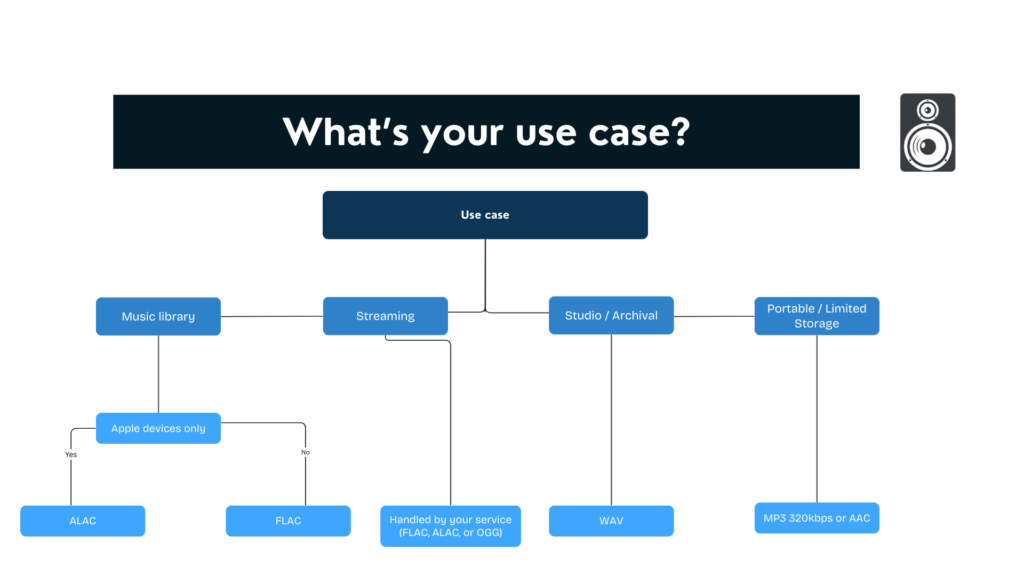

The right choice depends on how you listen, what devices you use, and how much storage you have.

For building a music library: FLAC is the standard recommendation. It’s lossless, widely compatible, half the size of WAV, and supports full metadata. If you’re on Apple devices exclusively, ALAC works just as well. Both formats let you convert to other formats later without losing quality, something you can’t do with lossy files.

For streaming: This is handled for you. Tidal and Qobuz use FLAC for hi-res. Apple Music uses ALAC. Spotify uses OGG. Amazon Music uses FLAC. Just make sure your streaming tier supports lossless if that matters to you. Most services require a premium subscription for hi-res streams.

For archival or studio work: WAV or AIFF for maximum compatibility and no processing overhead. When editing audio, you want zero CPU cycles spent on decompression, and WAV is universally supported across every DAW and audio application.

For portable devices with limited storage: You might still want lossy formats like 320kbps MP3 or AAC. The quality difference is subtle on earbuds in noisy environments, and you’ll fit far more music on your device.

For hi-fi listening at home: FLAC or ALAC streamed or stored locally, played through a quality DAC. This is where hi-res formats actually make a difference. If your setup includes a dedicated streamer, amplifier, and capable speakers or headphones, lossless audio lets you hear what that equipment can do.

What do you need to play Hi-res audio?

Having hi-res files is only half the equation. Your playback chain needs to support those files, or you’re not actually hearing the difference. Here’s what each component does and what to look for.

A Hi-res source

Your music source, streaming service, downloaded files, or physical media, needs to actually deliver hi-res audio.

For streaming, Tidal, Qobuz, Amazon Music Unlimited, and Apple Music all offer lossless and hi-res tiers. Spotify launched its Lossless tier in late 2025, though it maxes out at 24-bit/44.1kHz, just above CD quality. Check your subscription tier and app settings. Many services default to lower quality streams to save bandwidth, so you may need to manually enable lossless playback.

For downloaded files, purchase from stores that sell hi-res formats. Qobuz, HDtracks, and 7Digital all offer 24-bit FLAC downloads. Bandcamp has hi-res options for some releases.

A DAC that supports Hi-res

The DAC (digital-to-analog converter) takes your digital file and converts it to an analog signal that your headphones or speakers can play. Every phone, computer, and streaming device has a built-in DAC, but most are mediocre and cap out at CD quality.

New to DACs? Check out our guide that tells you everything you need to know about one.

For true hi-res playback, you need a DAC that supports 24-bit/96kHz or higher. Look for specs listing support up to 24-bit/192kHz or 32-bit/384kHz.

Portable DACs plug into your phone or laptop via USB-C and drive wired headphones. These make the biggest difference for mobile listening since phone DACs are typically the weakest link.

Desktop DACs sit between your computer and your speakers or headphones. They offer better components and more connectivity options.

Streaming DACs and music streamers combine a DAC with network streaming capabilities. Products like the WiiM Pro Plus, Cambridge Audio CXN100, or Bluesound Node connect directly to your network and stream from Tidal, Qobuz, or your own music library without needing a computer.

Headphones or speakers that reveal the difference

This is where people often overspend on files and underspend on hardware. A $2000 DAC won’t help if you’re listening with bad-quality hardware.

For headphones, look at models from Sennheiser, Beyerdynamic, HiFiMAN, or Audio-Technica. For speakers, bookshelf speakers from KEF, ELAC, or Q Acoustics paired with a decent amplifier.

Check out the AudioEngine HXL, a portable headphone amplifier and DAC.

Wireless headphones and Bluetooth speakers present a problem: Bluetooth compresses audio, so even if your source is hi-res, it gets downgraded during transmission. Sony’s LDAC and Qualcomm’s aptX Adaptive codecs get close to CD quality, but they’re still lossy. For true hi-res playback, you need a wired connection.

FAQs

Which is better, FLAC or WAV?

Sound quality is identical. FLAC is lossless, so it reconstructs the exact original. FLAC is generally better for storage and library management because it’s half the size and supports proper metadata. WAV is preferred in professional studios for compatibility and to avoid any processing overhead during editing.

Is FLAC or MP3 higher quality?

FLAC is significantly higher quality. MP3 is a lossy format that permanently discards audio data to shrink files. FLAC preserves everything. At 320kbps, MP3 is acceptable for casual listening, but it doesn’t compare to lossless audio on good equipment.

What is the best file type for high-quality audio?

For most people, FLAC offers the best balance of quality, file size, and compatibility. It’s lossless (no quality loss), compressed (reasonable file sizes), open-source (widely supported), and handles metadata well. WAV and AIFF are technically equivalent in quality, but with larger files and worse metadata support.

Is 192kHz better than 320kbps?

These measure different things. 192kHz refers to the sample rate (a hi-res specification). 320kbps refers to bitrate in lossy compression (like MP3). A 24-bit/192kHz FLAC file contains far more data and detail than a 320kbps MP3. They’re not directly comparable—one is lossless hi-res, the other is compressed lossy.

Why did Tidal drop MQA?

Tidal switched from MQA to FLAC in 2024 after MQA Ltd went through financial difficulties. The broader industry trend favors open formats like FLAC over proprietary ones. FLAC is royalty-free, universally supported, and doesn’t require special hardware for full decoding. MQA’s parent company has since been acquired by Lenbrook (owner of NAD and Bluesound), but its future role remains uncertain.